Polar Coordinates

Polar Coordinates

This isn’t strictly a calculus topic but it comes up a lot with calculus so I’m sticking it here. I’m not really sure what “part” of math coordinate systems belong to; they are used all over the place and have geometric and algebraic interpretations.

Definition

Polar coordinates are a 2d orthogonal coordinate system where coordinates are given by two components, radius and angle, i.e. $P = (r,\theta).$

The radius is the distance from the origin to $P$ and the angle is the angle formed with a line measured counter-clockwise from the positive $x$-axis to a line passing through $P$.

Converting Between Rectangular and Polar

\[x = r\cos\theta, \quad y = r\sin\theta\] \[r = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}, \quad \theta = \text{atan2}({y,x})\]Derivatives

If we parameterize such that $x = x(t)$ and $y = y(t)$ and want to find $x’$ and $y’$ in polar coordinates, we have:

\[\frac{dx}{dt} = x(t)' = (r\cos\theta)' = r'\cos\theta - \theta'r\sin\theta, \quad \frac{dy}{dt} = y(t)' = (r\sin\theta)' = r'\sin\theta + \theta'r\cos\theta \tag{a}\]thus:

\[\frac{\frac{dy}{dt}}{\frac{dx}{dt}} = \frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{r'sin\theta + \theta'r\cos\theta}{r'\cos\theta - \theta'r\sin\theta} \tag{b}\]Doing some tedious algebra from here, we can arrive at definitions of $r’$ and $\theta’$ in terms of $x, y, x’, y’ ~\text{and}~r$, but it’s easier if we start with the following, letting $x=x(t), ~ y=y(t), ~ r=r(t), ~\theta = \theta(t)$:

\[r^2 = x^2 + y^2, \quad \tan\theta = \frac{y}{x} \tag{c}\]Differentiating the first equation in (c) with respect to $t$ we get:

\[2rr' = 2xx' + 2yy', ~rr' = xx' + yy', ~ r' = \frac{xx' + yy'}{r} \tag{d}\]Rewriting the second equaton in (c) and then differentiating with respect to $t$ we get:

\[\theta = \tan^{-1}\frac{y}{x}, \theta' = \frac{1}{1 + {(\frac{y}{x}})^2} \cdot \frac{y'x-yx'}{x^2} = \frac{y'x-yx'}{x^2 + y^2} = \frac{y'x - yx'}{r^2} \tag{e}\]Summarizing (d) and (e) we have:

\[\frac{dr}{dt} = r' = \frac{xx' + yy'}{r}, \frac{d\theta}{dt} = ~\theta' = \frac{y'x - yx'}{r^2} \tag{f}\]Therefore, the derivative of $r$ with respect to $\theta$ is:

\[\frac{\frac{dr}{dt}}{\frac{d\theta}{dt}} = \frac{dr}{d\theta} = \frac{xx' + yy'}{r} \cdot \frac{r^2}{y'x - yx'} = \frac{r(xx' + yy')}{y'x - yx'}\]Radial and Transverse Components of Motion

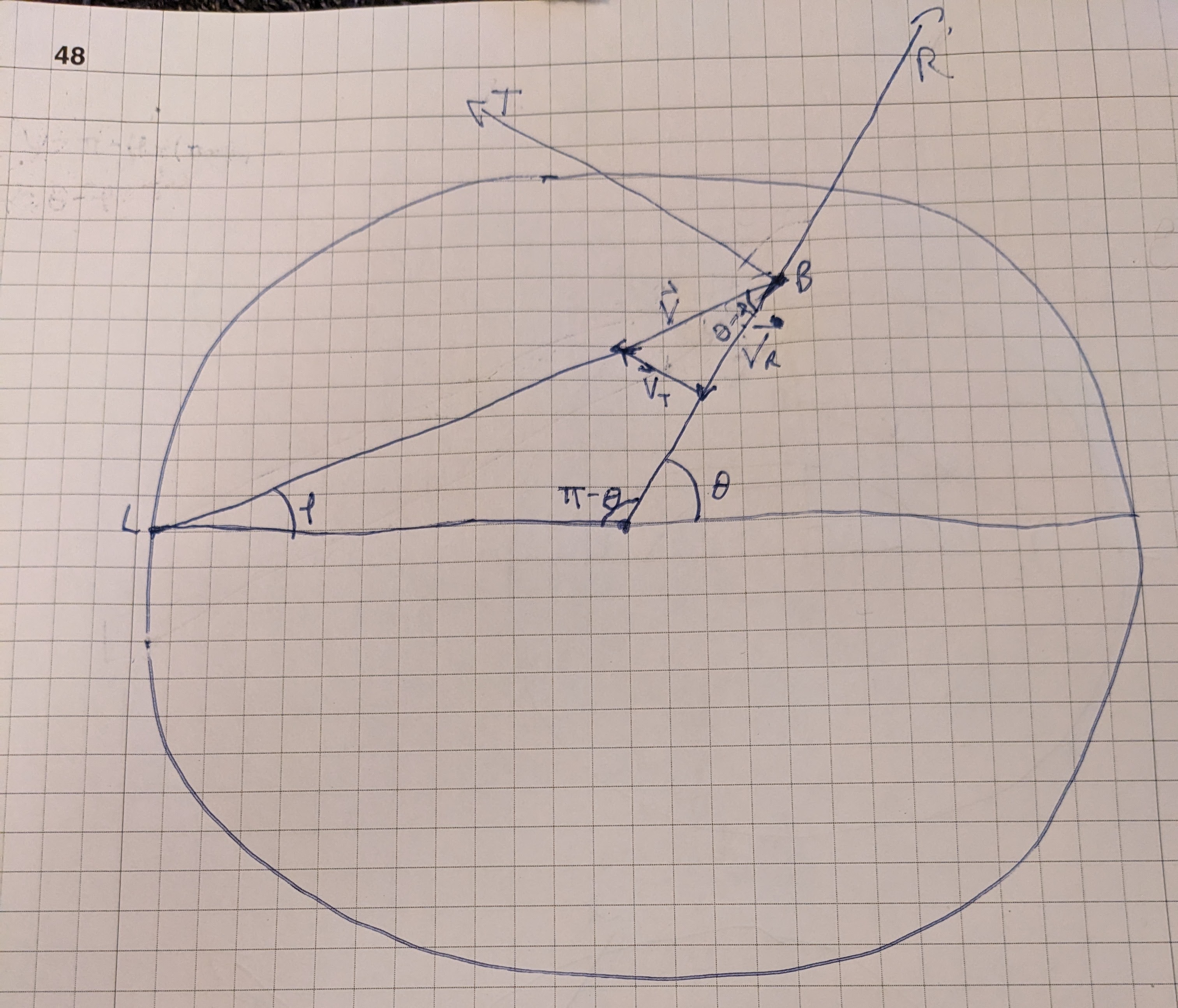

Given a particle at point $B(r,\theta)$ moving in a plane, we can define the radial and transverse components of the particle’s motion.

Radial: The particle’s motion in the direction away from the origin, that is, in the direction that purely increases the $r$ coordinate of the particle’s position.

Transverse: The particle’s motion in the direction tangential to its radius, that is, in the direction that purely increases the $\theta$ coordinate of the particle’s position.

Let’s call the radial direction $R$ and the transverse direction $T$. Also recognize that the radial and transverse directions are orthogonal - moving in the radial direction doesn’t change the transverse component and vice versa.

Let’s assume the particle at $B(r_1, \theta_1)$ is moving in the direction of point $L(r_2, \theta_2)$, at velocity $v_0$. We can then say that the velocity vector for the particle is given as the vector $\vec{v} = \langle v_0, \theta - \rho \rangle$.

Then, the component of $\vec{v}$ in the $R$ direction is the projection of $\vec{v}$ onto $R$, whose magnitude is given by $||\vec{v_R}|| = v_0 \cos{(\theta - \rho)}$, and the component of $\vec{v}$ in the $T$ direction is the projection of $\vec{v}$ onto $T$, whose magnitude is given by $||\vec{v_T}|| = v_0 \sin{(\theta - \rho)}$. The following image shows this geometrically:

Here, you can see that we can sort of think of the $R$ direction as the $x$-axis and the $T$ direction as the $y$-axis when thinking about how to find the amount of motion in the $R$ and $T$ directions. It’s important to remember, though, that for a moving particle, its position is changing constantly, and so are the $R$ and $T$ directions, so they don’t make good fixed references.

We must also point out that $\vec{v_R}$ is moving in the negative $R$ direction here and so is reducing the radius. In vector component form it would be given as $\langle -v_0 \cos{(\theta - \rho)}, \theta \rangle$ and the derivative of the radius with respect to time would be given by $\frac{dr}{dt} = -v_0 \cos{(\theta - \rho)}$.

Also, while $||\vec{v_T}|| = v_0 \sin{(\theta - \rho)}$, this doesn’t tell us the change in $\theta$ with respect to time, it only tells us the amount of linear movement in the tangential direction. The change in angle also depends on the radius - the further from the origin we are, the less the angle will change. The derivative of the angle $\theta$ with respect to time is then given by $\frac{d\theta}{dt} = \frac{v_0 \sin{(\theta - \rho)}}{r}$. Note: The division by $r$ here needs better justification. It’s intuitive that the bigger $r$, the less the change in angle, but it’s not clear why it should be a linear factor.

Other Notes

I found the notes in this document on converting a system of rectangular differential equations to polar coordinates particularly helpful.