Miscellaneous Types of Problems Leading to Equations of the First Order

Miscellaneous Types of Problems Leading to Equations of the First Order

First Order Linear Electric Circuit

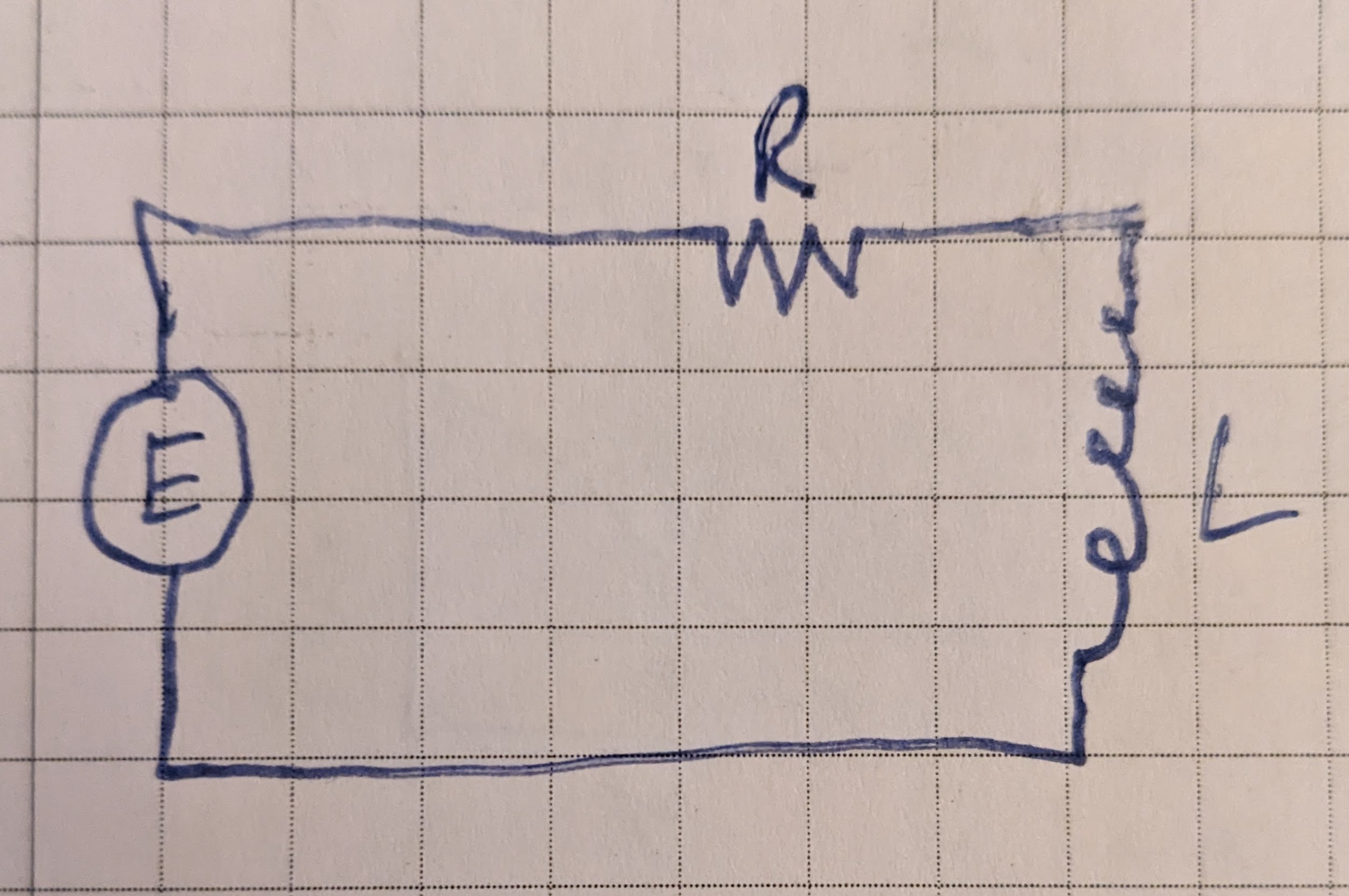

Take a circuit where an applied electromotive force $E$, an inductor $L$ and a resistor are connected in series:

The differential equation describing change in current over time is:

\[L\frac{di}{dt} + Ri = E \tag {17.63}\](jmh: my notes)

The above form is convenient for solving because it’s in the form of a linear first order differential equation. It says that the electromotive force equals the inductance times the change in current with respect to time plus the current times the resistance.

We could rearrange it to say:

\[\frac{di}{dt} = \frac{E}{L} - \frac{Ri}{L}\]Which says that the current changes over time by decreasing proportionally to the current current (hiyo) while growing by the electromotive force divided by the inductance.

The equation can be solved as a linear first order differential equation. This is straightforward and takes only a few steps when the emf is constant, resulting in the solution (for $t=0$, $E=E_0, i=i_0$):

\[i = \frac{E_0}{R}(1 - e^{\frac{-Rt}{L}}) + i_0 e^{\frac{-Rt}{L}}\]When emf varies sinusoidally with time the solution takes more work and is ($\omega$ represents the frequency of the sinusoidal wave):

\[i = \frac{E_0 (R \sin{(\omega t)}-L \omega \cos{(\omega t)} + L\omega e^{\frac{-Rt}{L}})}{\omega^2 L^2 + R^2} + i_0 e^\frac{-Rt}{L}\]This desmos link has graphs of the solutions when the emf is constant (DC) or varying sinusoidally with time (AC).

Some interesting things to note:

- For constant $E$, $L$ and $R$:

- We get a steady state current when the current grows enough that current loss caused by resistance equals the current growth caused by emf.

- This is makes the steady state current a sort of “terminal current” just like terminal velocity is the steady state where acceleration from gravity equals deceleration from air resistance.

- Increasing resistance reduces the peak current for both the DC and AC scenarios

- Increasing inductance decreases the rate of change of current for both DC and AC scenarios.

- For DC, this slows the ramp up/ramp down to the steady state current, which is $\frac{E}{R}$.

- For the AC circuit, the slower current change that comes from increasing inductance has the effect of reducing the peak current. This makes sense since the current is changing more slowly, it has less time to change before the voltage alternates and starts pushing the current back in the other direction.

- The lag in current change caused by the inductance brings the current out of phase with the emf. This is what results in the lower peak currents and is known as inductive reactance. Increasing inductance you can see that the current ends up being a quarter of a cycle behind the voltage.

- Decreasing inductance to near zero makes the DC circuit behave closer and closer to the ideal of Ohm’s law: $i = \frac{E}{R}$

Chain Hung over Frictionless Support

jmh: my notes

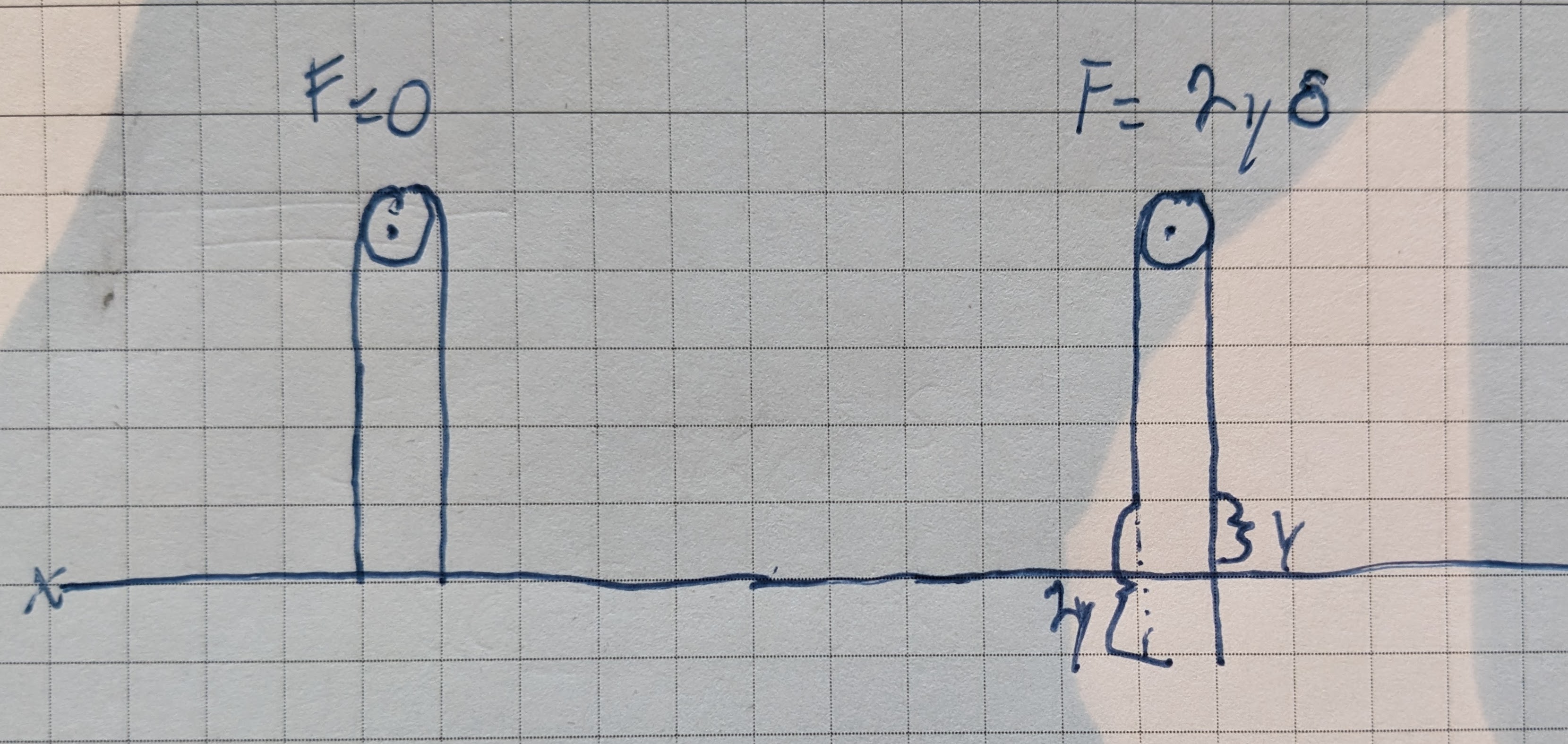

Consider a chain hung over a frictionless support. When the amount of chain on both sides of the support is equal, the chain is in equilibrium and doesn’t move. We can consider ends of the chain here to be hanging at $y = 0$, i.e. the $x$-axis. The chain doesn’t move because the force pulling the right side down (the weight of the chain on the right side) is equal to the force pulling the right side up (the weight of the chain on the left side):

\[F = ChainWeight_{right} - ChainWeight_{left} \tag{a}\]If we say that the chain weights $\delta$ units per ft and the length is given in feet we have:

\[F = \delta(ChainLength_{right} - ChainLength_{left}) \tag{b}\]Assume that the chain is adjusted so the portion on the right side of the support hangs $y$ below the $x$-axis. This means the portion on the right side must be hanging at $y$ above the $x$-axis and we have the force as:

\[F = 2y\delta \tag{c}\]

From Newton’s law of motion we have $F = mv \frac{dv}{dy}$ and so we have:

\[mv \frac{dv}{dy} = 2y\delta \tag{d}\]Here, $m$ is the total mass of the chain, which is the weight of the chain ($\delta L$ for a chain $L$ feet long) divided by 32 (to get slugs as the unit).

Excercise 17.23

Assume we have a chain 24 feet long hanging on a frictionless support with 14 feet on the right side and 10 feet on the left side. How long after release and with what velocity will the chain leave the support?

Using $(d)$ above, we have:

\[\frac{24}{32}\delta v\frac{dv}{dy} = 2y\delta,~ vdv = \frac{8}{3}ydy \tag{e}\]Integrating and solving for $v$ (taking the negative value of the square root to indicate downward velocity) gives:

\[v = -\sqrt{\frac{8}{3}y^2 + c_1} \tag{f}\]Substituting initial conditions $v = 0, y = 2$ we get $c_1 = -\frac{32}{3}$ and:

\[v = -\sqrt{\frac{8}{3}y^2 - \frac{32}{3}} \tag{g}\]The chain will leave the support when $y=12$. Substituting that value in (g) we get $v = -\frac{4\sqrt{210}}{3} \approx -19.3 ft/s$.

To find the time it takes for the chain to leave the support, we substitute $v = \frac{dy}{dt}$ into (g) to get a new differential equation:

\[\frac{dy}{dt} = -\sqrt{\frac{8}{3}y^2 - \frac{32}{3}} \tag{h}\]Rearranging and using initial conditions $t = 0, y = 2$ we get:

\[\int_{y=2}^{y=12} \frac{dy}{\sqrt{\frac{8}{3}y^2-\frac{32}{3}}} = \int_{t=0}^{t} dt \tag{i}\]The left-hand integral can be solved exactly using trig sub, but using numeric integration we find the approximate value of $t$ to be $1.51$ seconds.

Variable Mass Rocket

jmh: my notes

A rocket burns fuel to accelerate, causing its mass to be variable over time. To accomodate this, we need to make a small change to Newton’s law of motion $m\frac{dv}{dt} = F$ to get:

\[m\frac{dv}{dt} = F + u\frac{dm}{dt} \tag{a}\]Here’s what the values in this equation represent:

- $m$ - mass of the rocket at time $t$

- $v$ - velocity of the rocket at time $t$

- $F$ - sum of all the forces acting on the rocket at time $t$; usually gravity and sometimes drag

- $dm$ - mass leaving the rocket in time interval $dt$

- $u$ - velocity of $dm$ at the moment it leaves the rocket, relative to the rocket

The mass of the rocket at time $t$ can be given as $m = M + m_0 - kt$ where the values mean the following:

- $M$ - the fixed mass of the structure of the rocket

- $m_0$ - the initial mass of the fuel of the rocket

- $kt$ - the mass of the fuel burned by time $t$

Furthermore, differentiating $m$ with respect to $t$ gives $\frac{dm}{dt} = -kt$.

Rewriting (a) with these values and letting $u = -A$ to indicate the ejected $dm$ is moving in the opposite direction of the rocket we get get:

\[(M + m_0 -kt)\frac{dv}{dt} = -(M+m_0-kt)g + Ak \tag{b}\]Rearranging we get:

\[dv = (-g + \frac{Ak}{M+m_0-kt})dt \tag{c}\]Integrating with initial conditions $t = 0, v=0$ gives:

\[v = -gt -Aln(1-\frac{kt}{M+m_0}),~0 \leq t \leq \frac{M+m_0}{k} \tag{d}\]Which gives the velocity of the rocket at time $t$.

To find the position of the rocket at time $t$, we rewrite $v$ as $\frac{dy}{dt}$:

\[\frac{dy}{dt} = -gt -Aln(1-\frac{kt}{M+m_0}) \tag{e}\]Rearranging and integrating with initial conditions $t = 0, y =0$ gives:

\[y = At - \frac{gt^2}{2} + \frac{A}{k}(M+m_0-kt)ln(1-\frac{kt}{M+m_0}), ~0 \leq t \leq \frac{M+m_0}{k} \tag{f}\]Which gives the position of the rocket at time $t$.

More Reading

MIT has a great write up on the variable mass rocket equation.